The ankle joint provides the body with balance, stability, and the ability to bear the body's weight. It must do all these tasks while being exercised and manipulated over one million times a year.

Ankle sprains are one of the most common orthopedic injuries, occurring equally in both sexes and all ages. These injuries are most often reported by athletes; although it is not uncommon to see ankle sprains in those who suddenly trip on a step, slip without warning or ignore feelings of fatigue during exercise. There are over one million ankle injuries each year and approximately 85% of these injuries are ankle sprains.

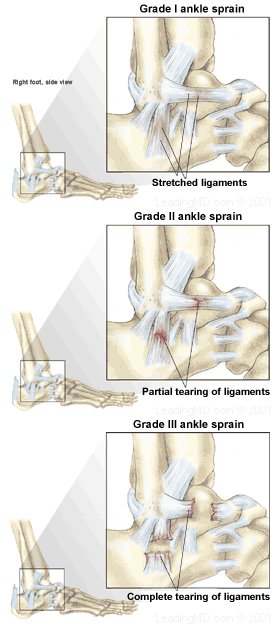

Ankle sprains occur in several forms: the high ankle sprain, the lateral ankle sprain, the medial ankle sprain, and the low ankle sprain. The high ankle sprain injures the ligaments connecting the two bones of the lower leg (the tibia and fibula) at the ankle joint. The medial ankle sprain injures the inside ligaments, collectively referred to as the deltoid ligament. The low ankle sprain involves the ligaments supporting the subtalar joint. This is the joint just below the true ankle joint. The subtalar joint is responsible for the foot's ability to turn to the inside and outside. Almost 85% of ankle sprains occur at the lateral (outside) aspect of the true ankle joint. This article will focus primarily on the most common type of ankle sprain: the lateral ankle sprain.

Overview

What are the signs and symptoms of ankle sprains?

The four symptoms common to all ankle sprains are:

- Pain

- Swelling

- Bruising

- Joint instability

Despite the varying severity of the symptoms, the strength of the joint may remain unaffected.

Pain

Pain is the most immediate symptom associated with ankle sprains. The pain has been described as "sharp" and "well-localized" to the affected area. Pain is usually worse with more severe injuries. This is often not the case in severe sprains with complete tears. With time the pain may become more generalized around the ankle. A feeling of burning and numbness from nerves that were stretched when the ankle was twisted may also accompany the sprain.

Swelling

Some degree of swelling will occur with any ankle sprain. In general, the greater the damage to the ligament, the greater the swelling. Swelling is the body's attempt to immobilize the joint. Other factors that can contribute to swelling are the tearing of a vein or failure to elevate the ankle following the injury. The swelling will vary depending on the response to raising the ankle in an elevated position. For these reasons, swelling cannot be used as an indication of the severity of the ankle sprain, as it will worsen if the extremity is not elevated for 24-48 hours after the injury.

Bruising

A black and blue discoloration over the injured area of the ankle usually occurs. This is caused by bleeding under the skin into the tissue. The degree of bruising is not a reliable indication of the severity of the sprain.

Joint Instability

When the ankle is severely sprained, there is commonly a feeling of "wobbling" or "looseness." Feeling a "pop" or "snap" in the ankle is a signal to stop activity and limit movement, as this may indicate a significant ligament injury.

How are sprains diagnosed?

Ankle sprains can be diagnosed in the doctor's office with a careful history and physical examination. Sprained ankles are often seen in the emergency room. Here, additional equipment is available to determine the exact location and severity of the ankle sprain.

Before examining the ankle, the physician will take a history (patient interview) to learn how the injury occurred. This will help to determine the type and severity of the sprain. A physical examination will assess the joint's stability.

- The physician can determine the location of maximum tenderness by pressing on the ankle.

- The physician will move the heel backward and forward to realign the ankle with the leg. This is known as the Drawer Test.

Further evaluation may include:

- X-rays to focus on the area of damage in the ankle. Stretching and tearing of ligaments won't show on X-rays, but X-rays are often taken to rule out an ankle fracture or dislocation. Mild sprains usually do not require X-rays.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) allows the physician to obtain an in-depth view of muscle and tissue not visible on an X-ray. MRIs are rarely performed for an uncomplicated ankle sprain.

- CT Scan(Computerized Tomography Scan): is another method used to diagnose the location of the ankle sprain. It provides detailed views of the ankle's ligaments at the site of injury. CTs are rarely performed for an uncomplicated ankle sprain.

Non-Operative Treatment

Most ankle sprains require Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation (RICE), followed by rehabilitation and muscle strengthening. When the ankle sprain is managed immediately with RICE, symptoms may be minimized despite the severity of injury.

Rest

Painful activities that may extend the injury or prevent full recovery should be avoided. When walking, a support or brace will help prevent re-injury. Ligaments heal best with minimal stress, so limited walking while protected by a brace or cast is recommended. Crutches are prescribed in most cases, but are not necessary in the recovery if the patient has a mild sprain that is immediately supported by a brace.

Ice

Ice is applied to reduce the amount of swelling and relieve the pain. Crushed ice placed in a waterproof plastic bag with a small amount of water is recommended immediately after injury. Crushed ice is preferred, as it easily conforms to the shape of the ankle and provides cold within the joint where the ligaments are located. The ice bag can be secured in place with an elastic bandage or plastic wrap. The skin should be monitored for frostbite. Ice should be applied for 20 minutes every 4 hours until the swelling stabilizes. A satisfactory alternative to crushed ice is a bag of frozen corn or peas wrapped around the injured ankle with plastic wrap. Heat is not recommended as it may increase the amount of swelling. Other alternatives to crushed ice are "instant ice" and frozen gel, but both of these options are not as effective as crushed ice.

Compression

Wrapping the ankle with an elastic wrap from the toes to above the ankle will give mild support. Most physicians prescribe an elastic bandage or brace that will compress and support the ankle. The additional pressure of the wrap further minimizes swelling. Taping of the ankle for less severe sprains will provide support and a level of confidence to the injured person as ankle movements are regained. Padding, such as six to eight layers of four inch square cotton pads or disposable diapers, should be firmly placed under the elastic wrap, as ankle sprains usually occur in areas where the wrap alone would be ineffective.

Elevation

The sprained ankle should be elevated above the waist to relieve discomfort and prevent additional swelling. The ankle should be propped up on pillows, especially at night.

Protection

Another important element of the non-operative treatment program is Protection. This changes the RICE formula to PRICE. Protection takes the form of casting or using a walking boot for the more severe unstable ankle sprain. A stirrup type brace (such as the Aircast Air Stirrup brace) is quite effective for protecting the majority of ankle sprains. Overall, the key to a successful treatment plan is early weightbearing, supported by a brace, and rehabilitation. In severe cases, a walking boot is prescribed for a few weeks and the patient is instructed to put weight on the ankle.

Medications

In addition to rest, the physician may recommend a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent such as ibuprofen to help decrease the pain and reduce inflammation within the injured ankle. Individuals with a history of drug sensitivity, known kidney or liver problems, or a bleeding disorder, should not use these medications. People with a history of stomach irritation or ulcers should not take anti-inflammatory medication without physician advice or supervision.

Operative Treatment

Potentially unstable Grade III sprains should be evaluated by an orthopedic surgeon within a few days of the injury. Surgery for a sprained ankle is rarely necessary, although some very severe sprains and some ankle fractures will require an operation. Most patients recover satisfactorily by following a non-operative treatment plan prescribed by their physicians.

In the case of a very severe ankle sprain which requires surgery:

- The incision is made directly over the area of the torn ligaments.

- The torn ends of the ligaments are identified and the joint is inspected for any debris.

- The ligaments are repaired with sutures or reattached to the bone with suture anchors prior to closing the skin.

- After the skin is closed, a protective splint is applied.

Post-operative immobilization is required for three to six weeks before rehabilitation begins.

Recovery from an ankle sprain is complete when the following goals have been met:

- Function is restored to the affected ankle.

- Joint stability and strength have been regained.

- Daily activities, including sports, can be completed without soreness, swelling and/or pain.

The length of time for recovery from an ankle sprain will depend on the severity of injury.

Mild sprains take 2-3 days before stiffness and pain subsides. Strict adherence to a proper treatment plan during the first day or two following the injury improves chances for a rapid and complete recovery. When walking, the ankle needs the support of a stirrup brace or splint.

Moderate sprains may require 1-3 weeks of treatment while gradually returning to activities. If, at this point, there continues to be swelling and instability during activity, an orthopedic surgeon should be consulted. Full recovery from ankle sprains should occur within 5-8 weeks of the injury. During this time, the ankle should be supported with a protective lace-up or stirrup brace.

Severe sprains require 6-12 months to heal completely. With protective taping and/or bracing, it is possible to resume athletic activity before this time, but the risk of re-injury is higher. Athletes should not return to sports until rehabilitation is complete, since risk for re-injury is great. A re-injury would make it less likely that the ankle would recover the same strength that existed before injury.

1. What is the difference between a sprain and a strain?

A sprain is the stretching or tearing of ligaments, which are the strong tissues that connect bone to bone across joints, such as the ankle. A strain, often confused with a sprain, is a stretching or overuse of muscles and tendons. A strain is often described as a "tight muscle." Strains occur within the muscles when there is not a significant amount of time given to stretching, or "warming up," the muscle before activity.

2. What causes an ankle sprain?

Ankle sprains are the result of a sudden twisting and pressure on the ankle. Sprains happen when normal range of motion in the ankle is disrupted. They occur for several reasons but the most noted are activities such as running on uneven pavement or stepping in a hole, jumping and landing on someone's foot, playing basketball, slipping on wet surfaces, wearing loose footwear or excessively using a fatigued joint. Not listening to the body when it is tired increases the chance for an ankle injury.

3. How can an ankle sprain be prevented?

Stretching before activity, strengthening the muscles of the lower leg, and improving skills will help to reduce the risk for ankle injury. This will also build strength within the joint. Strong muscles will improve performance, reduce the risk of injury, and improve range of motion. Learning proper technique for exercise will improve performance and help prevent injury.

The following exercises should be completed wearing athletic shoes:

- Alphabet Range of Motion: A simple stretching exercise involves lifting the foot in the air and "writing" the alphabet with the tips of the toes. Hold the big toe rigid so that all motion comes from the ankle. Repeat exercise hourly, if tolerated.

- Ankle Lift: Take a piece of rope about 1.5 feet long and tie a 5-pound weight to each end. Sit on a stool to allow the leg to dangle and place the rope over the top of the toes. Use the ankle to lift the weight as many times as possible.

- Ankle Turn: While sitting on a counter, take a long piece of rope and place it under the arch of the injured foot. Hold the ends of the rope at about knee height. Slowly pull on the inside of the rope while turning the ankle outward resisting the pull of the rope. Alternate inward and outward movements until the ankle is fatigued.

- Toe Raise/Heel Drop: Stand on a bottom stair or on a thick book with the forefeet on the raised surface. Rise up on the toes above the level of the stair or book, then return the heels below the level of the stair or book, so that the back of the lower leg is stretched. Lift and lower repeatedly, holding each position for 10-15 seconds. Continue until the calf muscles become fatigued.

In addition to these strengthening exercises, protective bracing or taping can be effective at preventing ankle sprains in athletes. Most important for the prevention of ankle sprains is realizing that fatigue and pain are signs from the body to stop activity and rest.

4. How long does it take for the sprain to heal?

In ankle sprains that are stable (no torn ligaments), activity can be resumed as soon as pain and swelling subside and confidence in joint stability returns. This can vary from a few days to a few weeks. When damage to the ligament is more severe, healing may take from 5-8 weeks following the injury. Following a severe ankle sprain, recovery can take from 6-8 months.

5. Can the athlete return to his/her sport before treatment has been completed?

It is not recommended that the athlete return to his/her sport prior to the completion of rehabilitation. Athletes must gradually increase activity. The chance for re-injury to the ankle is increased when recovery is not complete. Re-injury to the ankle will limit healing so that strength in the joint may not fully return to the pre-injury state. When treatment is completed, physicians recommend supporting the ankle by taping or using a re-usable lace-up brace for at least 6 months following injury.

1. Andersen, Bruce. Office Orthopedics for Primary Care Diagnosis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995, pp. 101-104.

2. Clanton, Thomas O. Athletic Injuries to the Soft Tissues of the Foot and Ankle, Coughlin, MJ and Mann, RA, eds. Seventh Edition. St. Louis, Mosby, 1999.

3. Garrick, James and David R. Webb. Sports Injuries: Diagnosis and Management. Second Edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.

4. Masear, Victoria. Primary Care Orthopedics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1996, pp. 117-122.

5. Veenema, Kenneth R. "Ankle Sprain: Primary care evaluation and rehabilitation," The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. September 2000, pp. 563-576.

6. Zimmerchik, John. Encyclopedia of Sports Science. 1997. Vol. II, 603-61