An acromioclavicular joint separation, or AC separation, is a very frequent injury among physically active people. In this injury the clavicle (collar bone) separates from the scapula (shoulder blade). It is commonly caused by a fall directly on the "point" of the shoulder or a direct blow received in a contact sport. Football players and cyclists who fall over the handlebars are often subject to AC separations.

An acromioclavicular joint separation, or AC separation, is a very frequent injury among physically active people. In this injury the clavicle (collar bone) separates from the scapula (shoulder blade). It is commonly caused by a fall directly on the "point" of the shoulder or a direct blow received in a contact sport. Football players and cyclists who fall over the handlebars are often subject to AC separations.

In general, most AC injuries don't require surgery. There are certain situations, however, in which surgery may be necessary. Most patients recover with full function of the shoulder. The period of disability and discomfort ranges from a few days to 12 weeks depending on the severity of the separation. Disruption of the AC joint results in pain and instability in the entire shoulder and arm. The pain is most severe when the patient attempts overhead movements or tries to sleep on the affected side.

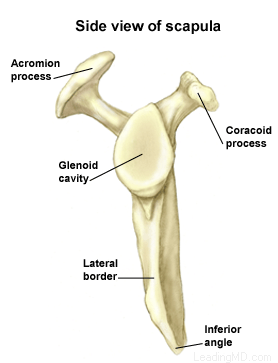

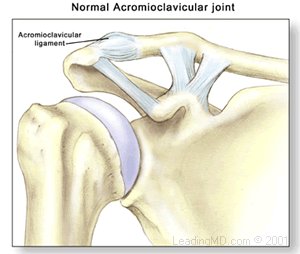

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body, with a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Several bones and a network of soft tissue structures (ligaments, tendons, and muscles), work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded.Click here to read more about shoulder structure.

What is an AC joint separation?

An AC joint separation, often called a shoulder separation, is a dislocation of the clavicle from the acromion. This injury is usually caused by a blow to the shoulder, or a fall in which the individual lands directly on the shoulder or an outstretched arm. AC joint separations are most common in contact sports, such as football and hockey.

The severity of an acromioclavicular joint injury depends on which supporting structures are damaged, and the extent of that damage. Tearing of the acromioclavicular ligament alone is not a serious injury, but when the coracoclavicular ligaments are ruptured, the whole shoulder unit is involved, thus complicating the dislocation.

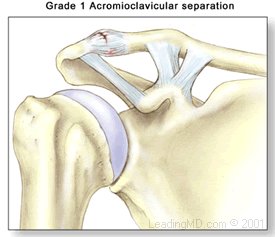

Simple AC injuries are classified in three grades ranging from a mild dislocation to a complete separation:

Grade I - A slight displacement of the joint. The acromioclavicular ligament may be stretched or partially torn. This is the most common type of injury to the AC joint.

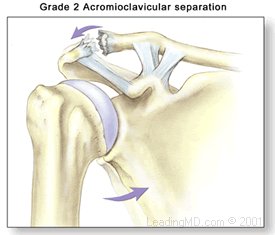

Grade II - A partial dislocation of the joint in which there may be some displacement that may not be obvious during a physical examination. The acromioclavicular ligament is completely torn, while the coracoclavicular ligaments remain intact.

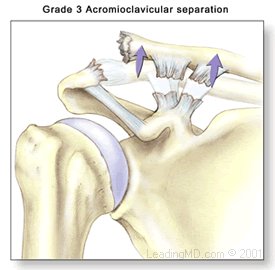

Grade III - A complete separation of the joint. The acromioclavicular ligament, the coracoclavicular ligaments, and the capsule surrounding the joint are torn. Usually, the displacement is obvious on clinical exam. Without any ligament support, the shoulder falls under the weight of the arm and the clavicle is pushed up, causing a bump on the shoulder.

There are a total of six grades of severity of AC separations. Grades I-III are the most common. Grades IV-VI are very uncommon and are usually the result of a very high-energy injury such as one that might occur in a motor vehicle accident. Grades IV-VI are all treated surgically because of the severe disruption of all the ligamentous support for the arm and shoulder.