Labral tears of the shoulder have been a particular focus of attention since the advent of the arthroscope, a small instrument that allows the orthopaedic surgeon to clearly see inside the shoulder joint and view the labrum, its environment, and any injuries that may have occurred. The arthroscope, in conjunction with anatomic dissections, history, physical examination, and symptoms has allowed orthopaedic surgeons to better understand and treat a variety of injuries to the labrum.

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

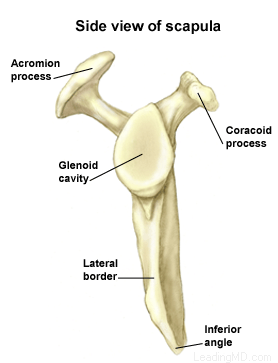

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body. It consists of a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Four bones and a network of soft tissue structures (ligaments, tendons, and muscles) work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded. Click here to read more about shoulder structure.

What is the labrum and what does it do?

The labrum is a disk of cartilage on the glenoid, or "socket" side of the shoulder joint. The labrum helps stabilize the joint and acts as a "bumper" to limit excessive motion of the humerus, the "ball" side of the shoulder joint. More importantly, it holds the humerus securely to the glenoid, almost as if suction were involved. Although the glenoid itself is a relatively flat surface, the labrum's cuff-like contour gives the glenoid a more concave shape. The secure but flexible fit of the humerus within the glenoid permits the great range motion of the healthy shoulder.

How is the labrum injured?

Tears of the labrum can be the result of:

- a direct fall or blow to the arm resulting in abnormal movement of the humerus.

- repetitive trauma of the greater tuberosity and rotator cuff on the posterior (back of) labrum. This is termed internal impingement (pinching of the soft tissues) and is most commonly seen in baseball and tennis athletes whose arms are frequently in overhead positions.

A very common labral injury is a tear that occurs on the top of the labrum, extending from the front to the back of the cartilage. This is known as a SLAP tear ("SLAP" is an acronym for superior labral anterior to posterior tear). This injury affects the attachment of the biceps tendon to the glenoid. An injury in this area can be extremely painful, and can cause the biceps tendon to rupture.

At least five types of SLAP tears have been identified. Treatment depends on the stability of the biceps anchor and the type of tear that has occurred. These injuries are commonly the result of:

- a fall on an outstretched arm.

- a forceful lifting maneuver.

- repetitive throwing.

It is very important for the surgeon to determine whether or not the labral tear is associated with instability of the shoulder. A tear of the labrum not associated with instability can be treated surgically by itself, but the treatment of a labral tear in an unstable shoulder will only be successful if the shoulder is surgically stabilized at the same time.

What are the signs and symptoms of a labral tear?

What are the signs and symptoms of a labral tear?  The physician will first take a history of the patient's injury in order to learn how it occurred. As mentioned earlier, the pain from a labral tear is located at the site of the injury, and is usually referred to as being deep inside the shoulder. A thorough physical exam may reveal other sources of injury or another disorder. During a physical examination of the shoulder:

The physician will first take a history of the patient's injury in order to learn how it occurred. As mentioned earlier, the pain from a labral tear is located at the site of the injury, and is usually referred to as being deep inside the shoulder. A thorough physical exam may reveal other sources of injury or another disorder. During a physical examination of the shoulder: