Frozen shoulder, or adhesive capsulitis, is a condition that begins with a gradual onset of pain and a limitation of shoulder motion. The discomfort and loss of movement can become so severe that even simple daily activities become difficult. Although much is known about this condition, there continues to be considerable controversy about its causes and the best ways to treat it.

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

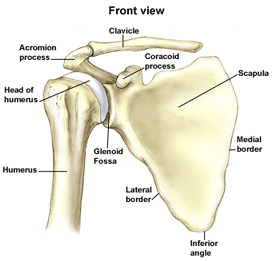

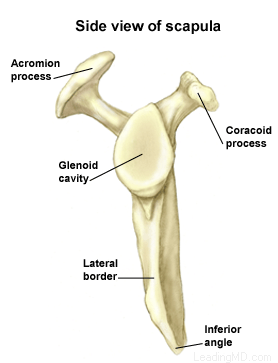

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body, with a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Several bones and a network of soft tissue structures (ligaments, tendons, and muscles), work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded. Click here to read more about shoulder structure.

What is frozen shoulder?

Frozen shoulder, also called adhesive capsulitis, is a thickening and tightening of the soft tissue capsule that surrounds the glenohumeral joint, the ball and socket joint of the shoulder. When the capsule becomes inflamed, scarring occurs and adhesions are formed. This scar formation greatly intrudes upon the space needed for movement inside the joint. Pain and severely limited motion often occur as the result of the tightening of capsular tissue.

There are two types of frozen shoulder: primary adhesive capsulitis and secondary adhesive capsulitis.

- Primary adhesive capsulitis is a subject of much debate. The specific causes of this condition are not yet known. Possible causes include changes in the immune system, or biochemical and hormonal imbalances. Diseases such as diabetes mellitus, and some cardiovascular and neurological disorders may also be contributing factors. In fact, patients with diabetes have a three times higher risk of developing adhesive capsulitis than the general population. Primary adhesive capsulitis may affect both shoulders (although this may not happen at the same time) and may be resistant to most forms of treatment.

- Secondary (or acquired) adhesive capsulitis develops from a known cause, such as stiffness following a shoulder injury, surgery, or a prolonged period of immobilization.

With no treatment, the condition tends to last from one to three years. Many patients are unwilling to endure the pain and limitations of this problem while waiting for it to run its natural course. Even after many years, some patients will continue to have some stiffness, but no serious pain or functional limitations.