Shoulder injuries are common in both young, athletic people and the aging population. In each of these age groups, there are numerous causes of shoulder pain. Two of the most common problems occur in the narrow space between the bones of the shoulder. Irritation in this area may lead to a pinching condition called impingement syndrome, or damage to the tendons known as a rotator cuff tear. These two problems can exist separately or together. It is likely that rotator cuff tears are the result of impingement syndrome and age related changes within the rotator cuff tendons.

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

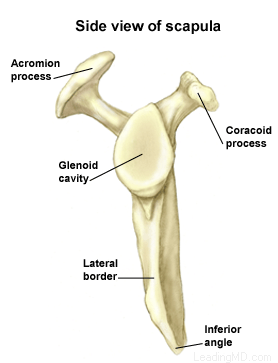

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body, with a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Several bones and a network of soft tissue structures (ligaments, tendons, and muscles), work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded.

Click here to read more about shoulder structure

What is impingement syndrome?

Shoulder impingement syndrome occurs when the tendons of the rotator cuff and the subacromial bursa are pinched in the narrow space beneath the acromion. This causes the tendons and bursa to become inflamed and swollen. This pinching is worse when the arm is raised away from the side of the body. Impingement may develop over time as a result of a minor injury, or as a result of repetitive motions that lead to inflammation in the bursa.

Particular shapes of the acromion may make certain individuals more susceptible to impingement problems between the acromion and the bursa. With age and the onset of arthritis, the acromion may develop bone spurs that further narrow this space. Impingement caused by bone spurs on the acromion is common in older patients who participate in sports or work activities that require overhead positions. Spurs may also result if one of the ligaments in the coracoacromial arch becomes calcified.

Impingement is classified in three grades:

- Grade I is marked by inflammation of the bursa and tendons

- Grade II has progressive thickening and scarring of the bursa

- Grade III occurs when rotator cuff degeneration and tears are evident

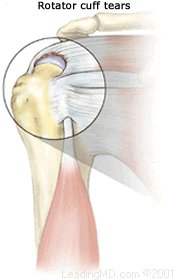

What is a rotator cuff tear?

Continual irritation to the bursa and rotator cuff tendons can lead to deterioration and tearing of the rotator cuff tendons. The tendon of the supraspinatus muscle is the most commonly involved tendon among the rotator cuff muscles. This muscle forms the top of the cuff and lies in the narrow space beneath the acromion. It is subject to the most pinching of all the rotator cuff muscles.

Rotator cuff tears can be the result of a traumatic injury or deterioration over time. Symptoms may be present, but in many cases, the patient experiences no symptoms at all. In young active people, full thickness rotator cuff tears are fairly uncommon. When they do occur, they are usually the result of a high-energy injury to the rotator cuff that is associated with throwing or overhead sporting activities. In older people, rotator cuff tears tend to be the result of wear and tear over time. Several scientific studies have shown that up to 2/3 of the population at age 70 have rotator cuff tears; many of these people had no symptoms.

What are the signs and symptoms of a rotator cuff tear?

What are the signs and symptoms of a rotator cuff tear? How are impingement and rotator cuff tears treated?

How are impingement and rotator cuff tears treated? Subacromial decompression expands the space between the acromion and rotator cuff tendons. This can be done either arthroscopically or with open incisions, depending on the preference of the surgeon. During an arthroscopy, a tiny fiberoptic instrument is inserted into the joint. In many cases, the doctor can assess and repair the damage through this scope without making large incisions. Scar tissue or bone spurs can successfully be removed with either technique. If a rotator cuff tear is found at the time of surgery, it can also be repaired if necessary.

Subacromial decompression expands the space between the acromion and rotator cuff tendons. This can be done either arthroscopically or with open incisions, depending on the preference of the surgeon. During an arthroscopy, a tiny fiberoptic instrument is inserted into the joint. In many cases, the doctor can assess and repair the damage through this scope without making large incisions. Scar tissue or bone spurs can successfully be removed with either technique. If a rotator cuff tear is found at the time of surgery, it can also be repaired if necessary. Rotator cuff repairs can be performed either arthroscopically or with open incisions. Arthroscopic techniques are new and limited to specific types of tears. An open repair that secures the rotator cuff tendons back to the humerus remains the surgical treatment of choice.

Rotator cuff repairs can be performed either arthroscopically or with open incisions. Arthroscopic techniques are new and limited to specific types of tears. An open repair that secures the rotator cuff tendons back to the humerus remains the surgical treatment of choice.