Glenohumeral (shoulder) arthritis is a common source of pain and disability that affects up to 20% of the older population. Damage to the cartilage surfaces of the glenohumeral joint (the shoulder's "ball-and-socket" structure) is the primary cause of shoulder arthritis.

Glenohumeral (shoulder) arthritis is a common source of pain and disability that affects up to 20% of the older population. Damage to the cartilage surfaces of the glenohumeral joint (the shoulder's "ball-and-socket" structure) is the primary cause of shoulder arthritis.

There are many treatment options for shoulder arthritis, ranging from pain medications and exercises for mild cases, to surgical procedures for severe cases. Treatment decisions are based upon the cause, the symptoms and the severity of the patient's disease. Each year, over 10,000 shoulder replacement surgeries are performed in the United States to relieve pain and improve function for shoulders that are severely damaged by glenohumeral arthritis.

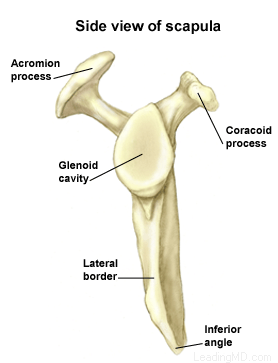

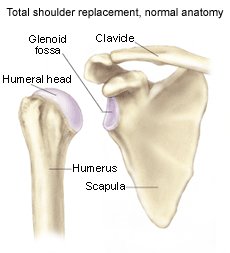

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body with a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Several bones and a network of soft tissue (ligaments, tendons, and muscles), work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded. Click here to read more about shoulder structure.

What is the labrum and what does it do?

The labrum is a disk of cartilage on the glenoid, or "socket" side of the shoulder joint. The labrum helps stabilize the joint and acts as a "bumper" to limit excessive motion of the humerus, the "ball" side of the shoulder joint. More importantly, it holds the humerus securely to the glenoid, almost as if suction were involved. Although the glenoid itself is a relatively flat surface, the labrum's cuff-like contour gives the glenoid a more concave shape. The secure but flexible fit of the humerus within the glenoid permits the great range motion of the healthy shoulder.

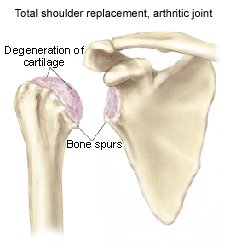

What is glenohumeral joint arthritis?

Glenohumeral joint arthritis is caused by the destruction of the cartilage layer covering the bones in the glenohumeral joint. This creates a bone-on-bone environment, which encourages the body to produce osteophytes (bone spurs). Friction between the humerus and the glenoid increases, so the shoulder no longer moves smoothly or comfortably. As osteophytes develop, motion is gradually lost. A number of conditions can lead to the breakdown of cartilage surfaces:

-

Wear and tear over time

Wear and tear over time - Trauma (such as a fracture or dislocation)

- Infection

- A chronic (long-standing) inflammatory condition (such as rheumatoid arthritis)

- Osteonecrosis (bone death caused by loss of blood supply)

- Chronic rotator cuff tears in which the head of the humerus (the upper bone in the arm) loses its proper position in the middle of the glenoid (socket)

- Rare congenital and metabolic conditions

- Post-surgical changes that can be a result of over-tightening during instability surgery