Shoulder instability develops in two different ways: traumatic (injury related) onset or atraumatic onset. Understanding the differences is essential in choosing the best course of treatment. Generally speaking, traumatic onset instability begins when an injury causes a shoulder to develop recurrent (repeated) dislocations. The patient with atraumatic instability has general laxity (looseness) in the joint that eventually causes the shoulder to become unstable.

Traumatic shoulder instability is most common in young, athletic people. The younger and more active the patient is when the first dislocation occurs, the more likely it is that recurrent instability will develop. For example, if the first dislocation occurs during the teenage years, there is a 70% chance that recurrent instability will develop. However, people over 40 with a first dislocation have less than a 10% risk of developing chronic instability. Treatment strategies should be designed to suit each patient’s age and lifestyle.

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

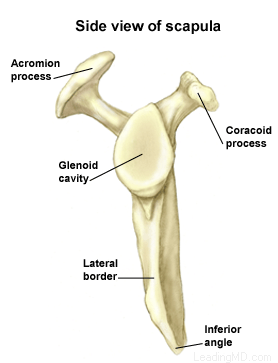

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body, with a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Several bones and a network of soft tissue structures (ligaments, tendons, and muscles), work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded. Click here to read more about shoulder structure

What is traumatic shoulder instability?

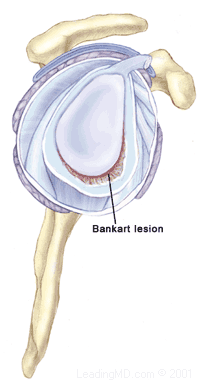

Traumatic shoulder instability begins with a first dislocation that injures the supporting ligaments of the shoulder. The glenoid (the socket of the shoulder) is a relatively flat surface that is deepened slightly by the labrum, a cartilage cup that surrounds part of the head of the humerus. The labrum acts as a bumper to keep the humeral head firmly in place in the glenoid. More importantly, the labrum is the attachment point for ligaments stabilizing the shoulder. When the labrum is torn from the glenoid, the support of these ligaments is lost. The development of recurrent instability depends upon the type and amount of damage that is done to the labrum and the supporting ligaments.

The most common dislocation that leads to traumatic instability is in the anterior (forward) and inferior (downward) direction. A fall on an outstretched arm that is forced overhead, a direct blow on the shoulder, or a forced external rotation of the arm are frequent causes of this type of dislocation. Much less common is a posterior (backward) dislocation, which is usually related to a seizure disorder or electrocution, events in which the muscular forces of the shoulder cause the dislocation.

X-rays are usually taken to confirm the dislocation, its direction, and to check for a related fracture. After the reduction, follow up X-rays will confirm proper positioning and assess any other injuries. X-rays may reveal a "bony Bankart", which is a fracture of the anterior-inferior glenoid (front, lower portion of the glenoid). The presence of this fracture indicates that the labrum and ligaments in the front part of the shoulder are no longer attached to the glenoid.

X-rays are usually taken to confirm the dislocation, its direction, and to check for a related fracture. After the reduction, follow up X-rays will confirm proper positioning and assess any other injuries. X-rays may reveal a "bony Bankart", which is a fracture of the anterior-inferior glenoid (front, lower portion of the glenoid). The presence of this fracture indicates that the labrum and ligaments in the front part of the shoulder are no longer attached to the glenoid. Open Labral Repair

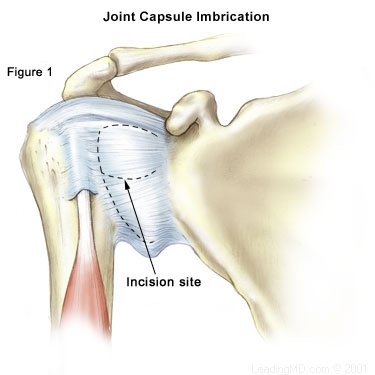

Open Labral Repair