Shoulder instability develops in two different ways: traumatic onset (related to a sudden injury) or atraumatic onset (not related to a sudden injury). Understanding the differences is essential in choosing the best course of treatment. As a rule, the patient with atraumatic onset instability has general laxity (looseness) in the joint that eventually causes the shoulder to become unstable, whereas traumatic onset instability begins when an injury causes a shoulder to develop recurrent (repeated) dislocations.

Atraumatic shoulder instability, also called multidirectional instability (MDI), is described as laxity of the shoulder's glenohumeral joint in multiple directions.

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

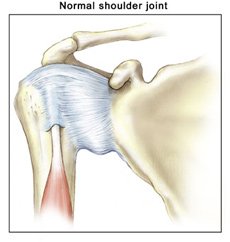

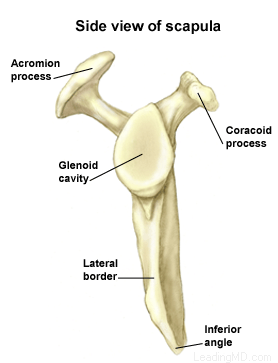

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body with a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Four bones and a network of soft tissues (ligaments, tendons, and muscles), work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded. Click here to read more about shoulder structure.

What is atraumatic shoulder instability?

What is atraumatic shoulder instability?

Atraumatic shoulder instability develops in patients who have increased looseness of the supporting ligaments that surround the shoulder's glenohumeral joint. The laxity can be a natural condition (present from birth) or a condition that has developed over time. Many patients with MDI are active in overhead sports (such as gymnastics, swimming, or throwing) that repetitively stretch the shoulder capsule to extreme ranges of motion.

The glenoid (the socket of the shoulder joint) is a relatively flat surface that is deepened slightly by the labrum, a cartilage cup that surrounds part of the head of the humerus. The labrum acts as a bumper to keep the humeral head firmly in place in the glenoid. It is also the attachment point for important ligaments that stabilize the shoulder. These ligaments often become stretched out with MDI, allowing dislocation or subluxation (an incomplete or partial dislocation) to occur. The increased motion of the joint can lead to repetitive microtrauma (small injuries), producing tears of the labrum or rotator cuff.

MDI patients will often have increased ligament laxity in many joints. Hyperextended knees, elbows, and a self-described history of being "double-jointed" are common. These patients often have multidirectional laxity in both shoulders. Because many athletes with MDI are quite successful in their sports, there is a debate about whether laxity improves performance or is caused by repetitive stretching during athletic activity.

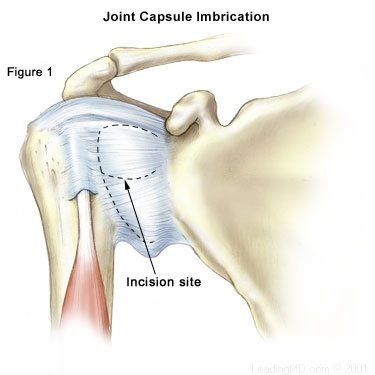

Traditional Approach

Traditional Approach